The truth behind “the coming tequila shortage”, and the real risks the industry faces

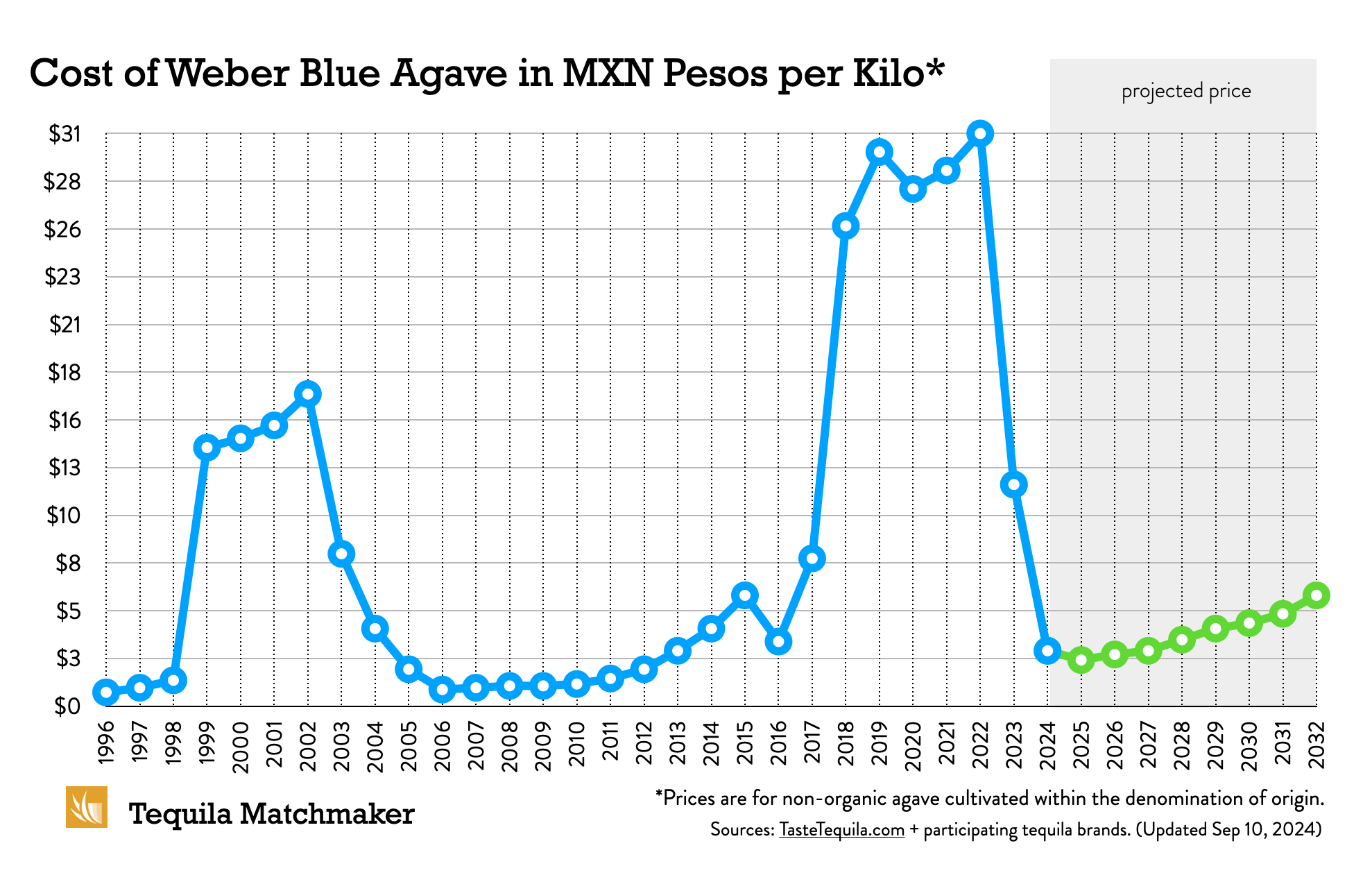

Here’s the good news on the “agave crisis”: We are reaching the peak. The bad news is we will likely experience a similar, or worse, situation in about 12 years. That’s because this cycle of boom and bust in agave availability and pricing has been happening since tequila was popularized.

Agave growers tend to plant more agave when prices are high, imagining the profits they will make when the plant matures in seven to eight years. But when that time comes, prices crash because there is much more agave available. So, the growers get disillusioned, they sell their crop for little or nothing, and decide to plant something else in their fields, like corn. Seven to eight years after that there is an agave shortage and prices skyrocket, and so the cycle continues.

“The story of boom and bust agave prices goes all the way back to the time of my great-great grandfather, 140 years ago,” says Guillermo Erickson Sauza, owner of Tequila Fortaleza.

“Around twenty years ago we had a similar peak at close to $1,600 USD per ton of agave, and four years ago it was below $25 USD per ton,” he said.

The difference this time around is that the effects of this cycle have been extended by increased demand, due to the global popularity of tequila, and some speculation on the part of the agave brokers and growers, who want to get the best prices they can for their crop while the price is high. (This is not unusual, of course, since you could say the same of many businesses.)

But, this time around these factors have agitated the normal tug between supply and demand, resulting in some of the highest agave prices seen since 2002 to 2003. Agave prices have already hit 22 pesos per kilo, when it was just 3 pesos/kilo just 5 years ago.

This situation has made for great headlines about an “agave shortage”, and even some talk that we risk “running out of tequila”, which has confused consumers. Some tequila lovers were left wondering if they should temporarily switch to another spirit, or risk doing the industry even further harm by creating demand when there is little supply. But these headlines have been misleading. There has been enough supply—albeit at high prices—but many tequileros are refusing to pay for it, and some even claim to have shut down production until prices drop.

“There is NO shortage, there is speculation,” says master distiller Felipe Camarena, maker of the G4, Terralta, and Pasote tequila brands, who also comes from a long line of agave growers. “I can get everything I want as long as I pay the price. People come to our distillery every day offering to sell agave.”

He, and other brand owners we’ve spoken with, feel that these suppliers have exaggerated the going rate of agave, and that some have decided to wait to sell until agave hits a certain high (like $25 MXN pesos/kilo), even if that means letting some of their plants rot in the field while they wait for their magic number.

However, agave farmers, such as Enrique Fonseca, believe that the price is, and always has been, based on the available supply and demand for agave at any given time.

“It’s the free market,” Fonseca says. “[Tequila makers] should stop buying at the high prices. If they can then get the prices to go down, then it would be true that there is no shortage, just speculation. But, I haven’t seen that lately. And I don’t think I will see that in this year, at least.”

Although tequila producers are predicting (hoping) that we’ve already hit the top, and agave prices cannot go any higher simply because it makes tequila production too expensive, Fonseca disagrees. Based on the 2001-2002 agave shortage, he believes that prices could go as high as $30-$33 pesos per kilo before coming back down.

The boom and bust cycle is a source of frustration for both agave growers and tequila producers, and with each high and low, tension becomes visible on one side or the other. Currently, it’s the brand owners who are feeling the most pressure as they struggle to stay alive while waiting for agave prices to drop. In a few years, it will be the growers.

Of course, some larger players in the industry either maintain their own crops, and/or have long-term contracts with their agave growers that set the price they pay, insulating them somewhat from the cycle. This is not the case for most smaller producers, who can’t commit to buying fields of agave at a time. The only way they can keep prices down is to own and harvest their own fields.

Dr. Adolfo Murillo has been growing agave on his family ranch for 25 years, and has experienced this cycle from the perspective of a farmer and a brand owner. He estimates that the break-even point for an agave farmer is between $2-$3 pesos per kilo. However, his tequila brand, Alquimia, uses only his own organic agave, which costs more to produce, but it’s still not as expensive as the current free market price.

“I have seen, too many times, a family invest their meager resources into buying plants, devoting their land to a promise of a good price, dedicating years of hard work, and many times going into debt to buy fertilizers, pesticides, weed-killers, and fungicides to keep their crop alive,” says Murillo. “Then, when it is time to sell, they find that the price is so low that they will not recover the money they invested.”

“While there may be a few companies that are completely self-sufficient, I think most are not,” says Erickson Sauza. “It takes a lot of land or partnership contracts to grow the agave necessary for our tequila industry. And, there is no quick solution to the problem.”

“Currently, we see three and four-year immature agave being harvested. This is because the growers are betting that the price will drop before their crop reaches maturity,” he added.

Some larger producers have been able to set their own rules, due to the value of their contracts. Although these contracts are often unfavorable during the high and low points of the boom and bust cycle, some are meant to bring some stability to the cycle.

Patrón, for instance, sets a minimum price to ensure the growers’ profitability even when prices are low, and then guarantees the current market rate when prices rise. This is all part of an effort to keep the growers in a more consistent business, rather than hedge on agave prices, a Patrón spokesperson confirmed.

Or course, there is another, newer industry player that is affecting this cycle—tequila makers who use diffusers. Diffuser production uses a giant machine commonly used to create agave nectar. It is a continuous process that can speed up the crushing, extraction, and conversion of starches into sugars in the most efficient way possible. Traditional processes require approximately 7 kilos of agave to create 1 liter of tequila, while diffusers only need 3.3 kilos to produce the same amount. They also don’t require the mature plants that traditional producers need. They can use four-year old agaves in a diffuser and achieve an even greater yield of fermentable sugars than a traditional producer can get from six to eight-year old agaves.

And while there has been a severe shortage of mature plants over the last year or so, younger agaves have been a bit easier to come by, giving diffuser users a slight advantage.

“[Diffuser producers use] baby agave plants which don’t require traditional planting, field maintenance and harvesting techniques, nor the communities sustained by those jobs,” says Jake Lustig, of Haas Brothers Spirits, and owner of the ArteNOM brand of tequilas.

Over the past two decades, this practice has been the main contributor to the reduction in the number of agave cultivators from over 25,000 in the 1990’s to fewer than 2,500 in the 2010’s, all while the category has tripled its production output, according to Lustig.

“The negative impact of chemical diffuser technology on rural economic sustainability, farmworker culture and heritage, and to the distillate itself simply cannot be overblown,” Lustig adds.

That’s a look at the current landscape. Let’s look to the future.

Where did we get the numbers used in the chart?

During the process of writing this story, and searching for historical numbers online, we realized that they didn’t exist anywhere. So we made contact with our industry friends (tequila brands, distillers, and agave growers who have been buying/selling agave through all of those years.)

In total, we received data from 4 brands, 3 distilleries, and 1 agave grower – all of whom kept records throughout the years. They agreed to share this data with us under the condition that we not release their identity. The information was fairly consistent among them all, so we averaged them all together to get the chart you now see here.

Once this chart was generated, we sent it to all of the parties who sent us data to confirm/fact check it, and they all agreed it was accurate.

If you wish to use this graphic, or the data we’ve collected, no problem. But please link to our story and be sure to credit TasteTequila.com as the source.

Agave Ahead!

Official statistics from the Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT) and the Camara Nacional de la Industria Tequilera (CNIT), indicate that the agave supply will increase dramatically over the next 5 to 6 years. By 2023 we should see an overabundance of agave, where the value of agave could be in the range of $1 MXN peso/kilo. Current projections indicate that by the year 2023 there will be 5 times the amount of agave available than the industry needs.

(These calculations were done including the agave needed to sustain the agave nectar industry.)

The Growers’ Side

It’s easy to understand why the smaller growers in particular would like to make as much as possible, while they can. Mexican tax rules require that single-estate growers pay a large tax bill on gross proceeds when their crop is sold, as if it were 100% profit, instead of being able to deduct expenses over the seven to eight years it takes for their crop to mature.

However, ongoing corporate entities and multiple-parcel owners don’t have this problem since they are making income from crops in different fields each year and are able to deduct expenses annually.

But now, in the boom cycle, growers have a different challenge—dividing up their proceeds into different corporate entities in order to take advantage of another Mexican tax rule that says if you are just a grower you are exempt of taxes from the first million pesos. This has lead to growers creating entities called “Sociedades de producción rural”, or “Sociedades”, that include multiple family members, allowing them to make millions of pesos, tax-free.

The Sociedad has the same benefit as a single grower, so if there are two members, for example, both are free of taxes for about 1 million pesos each. But the members can do that only if 90% of their income is coming from agriculture.

Some agave farmers are pulling in so much money right now that they are running out of family members who can claim ownership of their crops. Mexican tax law says that after the first $1 million pesos, a farmer must pay a 20% tax on the remaining income. Since they cannot deduct expenses incurred during the six to seven years it took to raise their crop, this is where they must pay themselves back. This is no easy task when the government takes their cut off the top.

And, given that the boom time will no doubt be followed by a bust, we can see why it’s important for growers to use any and all tax benefits they can find to save as much as they can. And, even that is often not enough. The historical pricing data shows that the bust cycle is now a lot longer than the boom periods, and for this reason many small family farms have found it impossible to survive.

The reason why the bust periods now drag on for so much longer than they used to is linked, in large part, to the use of modern diffuser-based production processes, where the necessity for quality mature agave is diminished.

“I believe the shortage will be extended due to the fact that a lot of agave buyers are purchasing very young agaves, some as low as 3-years old,” says Murillo.

The use of younger agaves by diffuser producers has a direct effect on brands using traditional processes, according to Lustig.

“There is so little mature agave remaining that the finer quality distillers [have to] drive up prices because of the limited supply,” says Lustig.

“The wide availability of cheap, diffuser juice has extended the time it would otherwise have taken to get to the final stage in this cycle,” he says.

Sustainability

While we are looking at a boom in agave availability over the next five to six years, some rightfully point out that this doesn’t address sustainability. There are a few issues affecting the long-term health of the industry, starting with the agave plant itself.

Almost all agave is produced using clones of the mother plant that are genetically identical. The problem with this is that if the plant is not allowed to evolve and mutate, it could become susceptible to a disease or pest that has the potential to wipe out a huge swath of the supply. That’s why some are calling for agave growers to allow the plant to pollinate naturally.

“For more than twenty years I’ve been trying to bring attention to this problem,” says David G. Suro, owner of the Siembra Azul and Siembra Valles tequila brands. “I don’t know anyone who plants from seed. If there is someone, I would like to meet them, and congratulate them!”

Making matters even more urgent are the effects of climate change, which has accelerated beyond anything this amazing 12-million year old plant has seen before.

“All living beings are suffering because of climate change,” says Dr. Benjamín Rodríguez-Garay, a researcher of plant biotechnology at CIATEJ Unidad Zapopan, specializing in the genetic improvement of the agave species.

He says that, with a stable environment, it would normally take about 800 years for a disease to evolve so that it can get beyond the agave’s immune system. But with colder winters and hotter summers, microorganisms and bacteria will find it easier to attack the stressed-out agave plants brought about by climate extremes, and dramatically shorten that period of time.

“Many people are suggesting that plants from seed produced by open pollination are the solution because the genetic variation is recovered. However, in the real life this will not work for the tequila industry,” says Rodríguez-Garay. “Instead, I propose to induce genetic variation by controlled pollination, and then select the good genotypes/phenotypes which have good performance under the new stressful environmental conditions.”

What Rodríguez-Garay is suggesting is the kind of genetic breeding that is done with other kinds of crops: identifying the plants that are doing well with today’s climate, then harvesting seeds for planting a portion of the crop to restore some form of natural protection.

“At CIATEJ we have developed protocols to do all of the above and we are working on these issues, as well as… many other Mexican institutions,” he adds.

But in the meantime it is still quicker and easier to continue with the common industry practice of using the genetic clones produced by the agave plants, despite the fact that it comes with risks.

“The practices that producers are currently using are not in the best interest of the industry, long-term,” Suro says.

We have heard rumblings from a few producers who say they plan to start experimenting with sourcing agave planted from seed, but no one has started quite yet.

Still, the fact that producers are taking sustainability more seriously is good news, but there is another essential ingredient to tequila production that is potentially at risk: the jimadores. These are the field laborers who do the back-breaking job of harvesting agave plants, often in intense desert-like conditions. Unlike just about every other part of the production process, harvesting agave cannot be done by machine. If the jimador population does not grow with demand, it will come with negative consequences for the tequila industry.

The job of jimador has traditionally been passed down from generation to generation, but because they do the same work in the boom period for the roughly the same pay as in the bust period, there is no financial incentive for future generations to continue in the family business.

“We are not generating any incentives for new generations of jimadores,” says Suro. “We have to, as an industry, create economic incentives for them to stay in the industry. We are doing a very poor job of creating those incentives.”

So, while this current “agave crisis” is really just part of a normal cycle, it could become a catastrophe in the future if we don’t pay attention to the health and sustainability of agaves, and properly incentivize the people who care for and cultivate them. But for now, enjoy your tequila. Many years, hard work, and passion for the spirit have gone into it.

How You Can Help

As a consumer, you can help simply by being aware of the current landscape, and rewarding the brands who are doing something to improve the situation.

Here are some ways you can be part of the solution:

Check the production processes of a brand before you buy. The Tequila Matchmaker app and website can tell you how a tequila was made. We all know that each production process has an influence on aromas and flavors in the final product, but they also have an influence on the industry as a whole.

Stop buying cheap tequila. With agave at $22 pesos/kilo, if a 1 liter bottle of 100% agave tequila is below $27, be suspicious. Unless the producer owns their own agave fields, and can produce tequila at a lower cost, odds are someone is getting cheated. It could be the farmer, the brand owner, or it could even be you.

There’s $9 USD worth of agave in the bottle alone. Add in the cost of the bottles, caps, labels, boxes, and it costs about $12.16 just to cover expenses at the distillery. Add another $15 for transportation, importation fees, distribution fees, and retail markup and you’re looking at $27/bottle for the brand owner to break even if they buy their agave on the free market.

Of course, brands that use diffusors can make tequila at a much lower cost whether they have their own fields or not, since it is an efficient process that can use fewer, and younger agaves. It’s up to you to decide if having cheap tequila is worth supporting the trend toward diffusors—for us, it’s not.

Spread the word. You get what you pay for. Teach other people about this issue, and encourage them to support brands that are doing something to help solve the sustainability issues outlined in this story. If you are a bartender, you’re on the front lines as an educator. Start by getting the mega cheap brands out of your well, and off of your bar.

Top notch article Grover. I’m going to forward it to anyone who might listen!

What is your take on Olmeca Altos which is retailing here in Marin for under $20? Are they taking advantage of the workers, growers? I thought their production was fairly “old school”. I don’t believe they use a diffusor. I definitely want to be socially responsible. :)

Great question, Chris. We are familiar with the brand’s products and they definitely do not have the aroma and flavor of a diffuser. We have no reason to believe this is in use, even though the price is lower than most.

There could be several reasons:

– They could be growing their own agave (or at least a portion of it)

– They may have stockpiled tequila when the price was lower, and are tapping into that now

– They may have a contract with agave suppliers that helps keep their price lower than market rate

All of these are just guesses, but we will try reaching out to the brand to find out.

Olmeca Altos is owned by Pernod-Ricard, who’s raking in the cash hand over fist from Jameson’s prolonged run. Avion also costs PR hardly anything to make and is extremely profitable. My guess is that they’re subsidizing the JDC Distillery and supporting master distiller Jesús Hernandez for the long haul, because he’s really one of the top-most expert producers/designers/distillers/thinkers/managers in the industry, would never use diffusers. French in this biz don’t seem to be such slaves to short-term margin as the folks across the channel, lots of examples of their patience with the long build..

Thanks, Jake. I’m trying to get a tour of the distillery, but haven’t heard back from the brand yet.

Good luck. I tried and failed to get inside. Let me know if you do.

Gordon Mott.

We are coordinating dates for the visit right now! Looks like this will happen soon.

I’m curious about that brand as well as it’s one of the most reasonably priced decent tasting bottles out there.

Yes , and please add Cimarron and Tapatio to that question . I feel these two brands are a great value and true old school tequilas .

As everyone knows by now, the Bacardi giant will buy out their remaining 70% stake in Patron Tequila some time this year for a whopping $5.1 billion. Founding member John Paul Dejoria will remain on board as their tequila ambassador. Since tequila is already popular in the USA, Bacardi’s goal is to bring tequila to the rest of the world.

So what does this all mean? Expect Bacardi to really lower their standards as usual just to increase production. This will eventually lead to an agave shortage unlike what was described in this article. This is downright terrifying! I have already begun stockpiling my favorite Tahona milled tequilas.

Is this happening? Any update on this?

The pricing graph is regularly updated.

Great article extremely well done and great references. I’m the CEO and founder of Mezal Amaras and I can’t agree more with all the sustainability aspects you mentioned. You should check the philosophy we have In our webpage for planting and sustainability , we are covering all the main problems you mentioned plus having organic planting because another massive problems the blue agave is facing of the amount of pesticides that their are using which accumulates in the plant and affects not only the growth of the agave but as well the final consumer that is taking all those chemicals. I believe that’s a massive difference in the hang over because the toxicity of the product, due to all the chemicals they are adding.

Another important issue is how the lack of planning and sustainability in the tequila industry is affecting the mezcal. Tequila producers are breaking the rules by going to Oaxaca and buying Espadín because the price of agave is always cheaper in Oaxaca. Due to this the price of espadin went from

30 cents to 12 pesos a kilo in the last 5 years. This is affecting the whole industry and popularity. Because mezcal is becoming extremely expensive to produce because to make one liter you need around 10 to 11 kilograms of agave. As well is affecting the wild agaves , because local producers can’t afford to buy espadin and they are over consuming the wild agaves in their region because is cheaper for them to go and harvest them on the will. This will create a massive shortage on the will agaves for the future.

Other states and agaves are having similar problems , I was in guerrero last Friday and teauileros are also using agave cupreata for the production of tequila.

It’s a mess for all the people this lack of planning and suitability in the tequila industry I hope one day peaple follow good practices on order to create a fair industry for alll.

If you want more info please don’t hestiate to look for me.

Another fantastic and informative article about the current and past agave situation, many of the factors involved, and what we can do to help. I couldn’t agree more, than to support brands that produce traditional quality-made tequila, and are concerned and involved in the current and future plans for tequila. People like David Suro, Carlos Camarena and other quality producers like Felipe Camarena, and Adolfo Murillo are key players, and do it right. It is very tough for the smaller brands that don’t grow their own agaves, but still maintain their quality product, but at a higher expense to them. We need to do all we can to keep them afloat. Staying away from all diffuser brands is a necessity, especially at this time, and refusing to buy cheap tequila either in a bar (ask what is in the well) is as important as what you buy for home use, even to use as a mixer. I agree that everyone should always check Tequila Match Maker to learn how a product is made. I know the passion Grover puts into this App, making it the best source for referencing agave distilleries and much more. Thanks Grover for another excellent article.- Lou Agave of Long Island Lou Tequila

Hi Grover, excellent article. I am an agave grower myself and am very happy to have good prices for our produce that takes a lot of work, time and money.

The big tequila companies will always make tons of money, they always have. Not us and we supply the raw materials. I also am aware of what I call “the wave” ie everybody plants when prices are high loose their shirts when prices are low, this is when tequila producers buy cheap agave and store in tanks and barrels. This is just a matter of time. They will always sell their tequila.

You made a very important point, that agave producers should have a tax plan with SPR companies = (sociedades de produccion rural). Otherwise the agave producers will pay inmense taxes on their agave sales.

Great write up. I was curious, because you didn’t define what a small grower is, acre-wise. how many acres would you consider for a small grower, medium grower and large grower.

I ask because I have 100 acres right behind the the Embajador distillery between La Purisima and Atoto. I don’t control it yet but the ranch is titled to my name. When the time comes, I want to cultivate and have my own distillery.

Thanks

That would be a dream come true for me!

I think the term “small grower” is more like an independent farmer who doesn’t depend 100% on agave sales for income. Sure, sizes of the land always vary, but if you’re planting 10 acres of agave in the land next to your house as a way to supplement your family’s income, I’d consider that small.

FELICIDADES POR EL ARTICULO GROVER GROVER, DIFIERO TU PUNTO DE VISTA SOBRE EL DIFUSOR, ES VERDAD QUE EFICIENTIZA LA EXTRACCIÓN DE LOS AZUCARES, PERO ESTAN LAS SIGUIENTES ETAPAS, HIDROLISIS, FERMENTACION,DESTILACIONES Y MADURACIONES, TODO EL CONJUNTO DE OPERACIONES HACEN EL TEQUILA Y EL MAESTRO TEQUILERO FIRMA EL ARTE. ES COMO SI TE DIGERA GROVER, MANDAME UNA CARTA Y NO USES EL TELEFONO CELULAR.

SALUDOS.

MRC

CONGRATULATIONS FOR THE ARTICLE GROVER GROVER, DIFFERENT YOUR POINT OF VIEW ON THE DIFFUSER, IT IS TRUE THAT EFFICIENCY THE EXTRACTION OF SUGARS, BUT ARE THE FOLLOWING STAGES, HYDROLYSIS, FERMENTATION, DISTILLATIONS AND MATURATIONS, ALL THE SET OF OPERATIONS MAKE THE TEQUILA AND THE MASTER TEQUILERO SIGNS ART. IT IS LIKE IF YOU KNOW GROVER, SEND ME A LETTER AND DO NOT USE THE CELL PHONE.

GREETINGS.

MRC

Really great article! I appreciate the “what you can do” section at the end. It always frustrates me to have a problem(s) pointed out but to be left with no solution or way to make an impact on the issue.

One question. I’ve yet to find a distillery in the database listed as “Diffuser” (even when searching suspect brands such as Exotico). Can someone point out an example of a brand (distillery, NOM) on the site using this method?

I was lucky enough to attend a seminar here in Colorado last year at which the great Enrique Fonseca was speaking. This was the first I’d ever heard of Diffusers and I’ve been a part of the industry for over a decade. It was a great seminar and I left with unique insight from an important producer, but it seems everyone is a bit tight lipped about who is using the diffusers? Another interesting piece of information I picked up was that the NOM on the bottle doesn’t necessarily guarantee that distillery actually distilled the juice in the bottle, only that they’re taking responsibility for it. Quite a few caveats in the tequila world, and navigating them is somewhat confusing. I’d love to be able to pass on as much info as possible to my my customers concerning both what to support, and what to avoid.

Thanks and keep up the good work!

Hi Andrew – We show the production information on the tequila product profile, not the distillery profile. Here are a few examples of diffuser-made products:

Cazadores

http://tequilamatchmaker.com/tequilas/2545-cazadores-tequila-blanco

Sauza Tres Generaciones

http://tequilamatchmaker.com/tequilas/2644-tres-generaciones-plata

Casa Dragones

http://tequilamatchmaker.com/tequilas/4140-casa-dragones-sipping-tequila

Interesting, I didnt realize some of the “high-end” producers were using this method. It’d be cool to be able to filter searches by data like this. Remember when all that was important was that it was made from 100% agave?.. Thanks for the info!

Great article, Grover. I’m of the firm belief your article left out a key player in the blue agave industry – the mieleros (agave syrup industry). As a blue agave owner of 5 lots in Nayarit and Jalisco, the mieleros often buy it at a better price than the tequila distillers. The average blue agave nectar company mashes 80 tons per day which translates to roughly 29 million kilos of agave per year for just one company (Mieles Campos Azules S.A. de. C.V. for instance). Multiply that by all the ones that exist in Mexico and you have yourself a competitor that affects the price per kilo of the plant. I’m very positive that these variables would affect the graph provided on your article.

Thanks for adding this, Gerardo. When we calculated the pricing estimates for the graph, it included the amount of blue agave used by the nectar producers. This information was provided by the CRT and the CNIT.

What’s your outlook now Grover? Ever since I have read this article (September) I thought the forecast was short. I had a simple; maybe naive, calculation for the top price for Agave. From early 2002 the dollar price agains Mexican peso was 12pesos/USD dollar and the maximum price reach was 1.5USD per kg 18 pesos/kg. This time it would had to be around 30pesos/kg MAX since the exchange was close to 20 at the time of this publication. Today agave azul is being bought at 38pesos I think we are at the top. Unless the new government in Mexico keeps shaking the economy.

Wow, $38 pesos? I haven’t heard it reaching that point yet. I’ve been getting steady reports of $25 pesos/kilo and then last week 1 person reported paying $30 pesos. But $38 pesos is beyond anyone’s wildest expectations. Where did you get that number from?

I’ve also been hearing that there are 2 things going on that are intensifying this cycle (forcing it higher AND causing it to drag on longer): 1) the demands of the agave nectar industry, and 2) diffuser production methods harvesting agaves at 3 and 4 years old.

At $38 pesos/kilo, a whole lot of tequila brands will vanish from the market.

I am sorry I meant, 28 pesos. Finger error.

I am happy the forecast got updated in this article on July, 2019 that matches a bit more on what I was inferring in my initial comment. “This time it would had to be around 30pesos/kg MAX “.

I do believe we will see this prices for 2020 and 2021, with a meaningful correction for 2022 but not as sharp as your forecast. I think by 2023-2024 the new low will be around 10-16 pesos, the impact of the “mieleras” will continue to keep the agave prices on higher lows for the next decade.

I would love to hear your toughs.

This comment is aging well.

We are currently at $32 pesos,maybe that chart needs a new update. Price will flatten by 2021-2023, around that same price.

2023 we start harvesting all the 2016-2018 agave and prices start “maybe” going under 25.

Indeed aging well…. Will be interesting to see the prices in the next coming years.

Great article, Grover. In the spirit of being a responsible consumer, I’d love to see a feature in the Tequila Matchmaker app that allows me to screen out the diffuser produced brands. Or maybe a better way to do it would be to allow the user to browse tequilas and filter by production method. Just a thought.

Hi Darren. We are working on that right now, but it will be in the form of a very advanced search feature on the Tequila Matchmaker website.

I’d like this too, in the name of educating myself & customers. Filtering options in the search would be great, and the diffuser option in particular.

Hi Mr Grover!

I am a agave grower in the state of Jalisco: I have interest in 4 different fields with agave plants ranging from 4, 3, 1 yr old plants. I got to say that I was pushed out of the market back in 2006-2008 due to low agave prices and lack of demand.

( I had approx 150,000 plants with various maturity ages). Learned about the process; Importing to the US requirements; IMPI requirements to register own brand in Mexico; Learned about the whole agave-tequila industry! Was a few months short (late) of potentially supplying Costco with agave to manufacture their Tequila brand (“Kirkland”).

My experience tells me that you need to love, nourish the process to be in the industry. I feel grateful that I provided employment (2001-2008) and provide now to a few of my relatives and town friends . For them it could mean their lively hood and not wanting to migrate to “El Norte” (US) and risk their lives crossing the border undocumented.

The big Tequileras, always have the advantage over the agave producers (i. e. use of diffusers, it takes 1/3 of the agave to make 1 ltr of 100% tequila) not to mentioned control over the CRT ( I believe the CRT is funded by the Tequileras, 1$ peso per ltr of tequila mfg to the CRT)( the figures they provided to you of agave plantations / numbers could be “skewed”.

…anyway, I felt that I need to brainstorm and comment my 2 cents. Enjoy Tequila, enjoy life, Salud!

P.S. I am producing / marketing organic fertilizer, high silica SiO2 content.

Grover,

This was a great article. Thank you!

I was wondering if you had a sense for how much yields are down? I know that one of the issues (as you mentioned) is that producers are harvesting younger plants. I’m trying to better understand this dynamic. For instance, if agave used to cost, let’s say, 10 pesos/kilo and you needed 1m kilos ($10m pesos going out the door)….it’s now 25 pesos/kilo but I imagine you need to buy a lot more kilos (or plants?) given the lower yields. Just trying to understand how much the cost for the brand owner (who’s not integreated) has gone up. Any thoughts on this would be much appreciated.

I also was curious how much agave is required to make 100% and mixto. I thought it was something like 7 kg/L for 100% and 3 Kg/L for mixto. Does that sound about right?

Great questions. Let me answer the last one first.

Our data, from a survey of 11 different distilleries, shows that the average yield is as follows:

Traditional Process: 7.433 kg/L

Diffuser Process: 3.75 kg/L

Diffuser producers don’t really care if the agave is mature or not. They are the ones taking the young agaves. The yield is the same, they are just using more plants.

Traditional producers don’t have the luxury of using immature agaves, they must use agaves of at least 6-years of age.

Thanks! A few more questions:

1. What’s the average yield in Kg/L for mixto? Is that what’s meant by diffuser?

2. Would someone like Jose Cuervo be a diffuser? I ask because I’ve read about that harvesting younger agave plants.

3. If the yield stays the same, is it that younger plants simply weigh less and that’s why more plants are required? If so, what’s the weight of an average mature plant (20-30 kilos?) vs one that might be only 4-5 years old?

Very helpful!

1. Not sure about mixto. It’s not the same as diffuser. Mixto has at least 51% blue agave sugar, and the remaining 49% can be super cheap cane sugar. Depending on the ratio of agave:sugar used, it will be different.

2. Yes, Jose Cuervo uses a diffuser. So do a lot of brands. Here’s a list of products known to use a diffuser: https://www.tequilamatchmaker.com/tequilas?q=&hPP=30&idx=BaseProduct&p=0&fR%5Bcrushing%5D%5B0%5D=Diffuser

3. Yes. Average weight of a fully mature plant can vary greatly based on growing conditions, from 35-100 kg, with most averaging around 35-45 kg. Immature agave? Good question, since some distilleries are using 3 and 4-year old plants, they haven’t had much time to put on weight. For a 4 year old plant, it should clock in below 20 kg — between 15 and 18 kg.

Thanks Grover! Last question for now – this has been very helpful! I’ve read a few quotes to this effect, “The younger plants produce less tequila, meaning more plants have to be pulled up early from a limited supply – creating a downward spiral.” Is there a way to think about how much less tequila the younger plants produce (like a 4 year old plant)? That’s why I was asking about weights. For instance, this is how I was thinking about it: let’s say your a brand and you produce 5m liters of tequila 100%. Assuming 7 Kg/L means you would need 35m kilos of agave. Assuming an average plant weighs 30 kilos, you would need ~1m mature plants. By contrast, if a 4 year old plant weighs 17 kilos, you would need ~2m immature plants. So double the amount of plants required….is this the right way to think about it?

Grover, un amigo me envió tu link.

Interesante la investigación que han realizado, bastante ilustrativa.

Saludos

Sergio Moran